Not because of changing consumer tastes or market forces, but something altogether more sobering: sewage. Since mid-April, more than 1,000 cubic metres of wastewater, some of it reportedly triggered by as little as 10mm of rain, has flowed into these waters. Norovirus has been detected. Oyster harvesting has stopped.

This isn’t just bad news for the region’s farmed oysters. It’s devastating for the people who farm them, who run small, often family-run operations that have been tending to the harbour for years, even decades, selling at local markets, building reputations oyster by oyster. These are not just businesses: they’re livelihoods; they’re identities; their relationship with the sea is longstanding and often deeply personal.

The farmers point to a predictable culprit: underinvestment in infrastructure. As Warkworth and its surrounds grow, the pipes and pumps meant to support it haven’t kept pace. Watercare, the council-controlled organisation responsible, acknowledges the system needs work. A fix is coming, they say, but it’s still 2-3 years away.

In the meantime, the water is presumed unsafe for aquaculture and the farms are closed with the farmers offered no compensation. There appear to be no public warning signs to inform swimmers or boaties. Some claim the Mahurangi has quietly been reclassified as ‘non-recreational’, a bureaucratic sleight of hand that sidesteps the need for public health signage.

So where does that leave us?

At the junction of food, politics and environment. Oyster farming is often held up as the poster child of sustainable aquaculture; it filters water, it creates habitat, it demands little. But it turns out it’s vulnerable to everything upstream such as wastewater, planning decisions, council priorities and the slow wheels of infrastructure investment. What happens when small industries – especially those that benefit the environment – become collateral damage in urban expansion? And when things go wrong, who is held accountable?

The community has launched a petition, demanding action, transparency, and accountability (chng.it/JxBpXtsWjw)

Because while oysters may seem like a niche concern, this is not a niche issue. This is about how we grow as a nation. About what, and who, gets protected. Do we want a future where growth is planned and sustainable, or one where short-term gains leave long term damage. It’s about whether we value the long-term health of our waters – and the small, good things they give us, like a perfect, briny oyster – enough to fight for them when it counts.

It’s worth thinking about.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Cuisine Cheese Watch / Anabelle’s Garlic and Herb Bouchées

Anabelle David is a French-born Kiwi on a mission to share her love…

Inspirational Women in Food & Drink

New Zealand’s food-and-drink industry is filled with hardworking and…

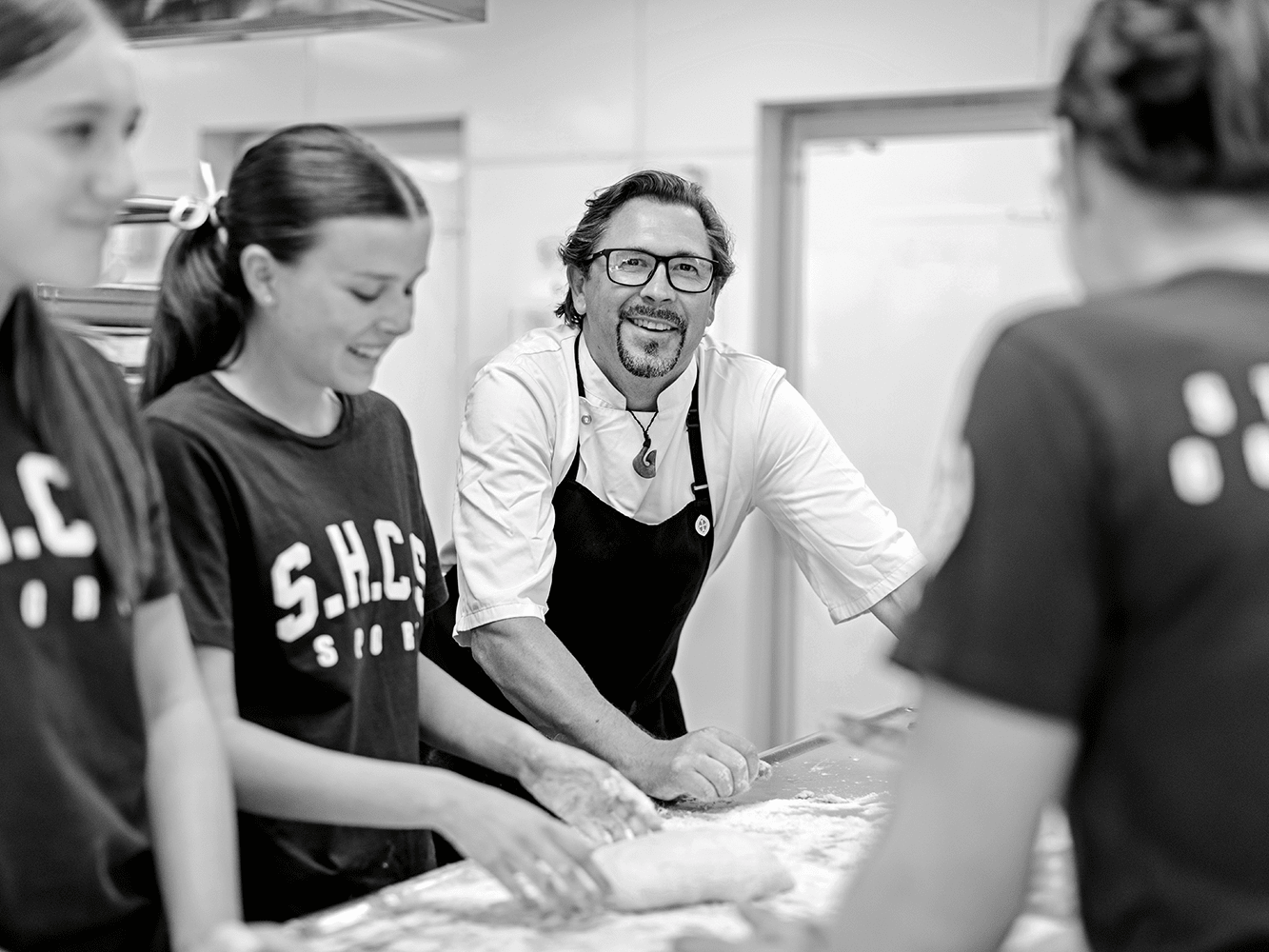

We’ve Noticed…. Marcus Verberne

Cooking skills open up a world of different opportunities. From fine…