From mystery to blockbuster, Elizabeth Latham considers food tourism and how we should be telling (and selling) our food experiences.

We’ve got it! Fabulous food from Stewart Island to Northland: blue cod in Southland, tomatoes in Kakanui with a wedge of Whitestone cheese, smoked fish in Mapua, asparagus in Levin, oysters on Waiheke, to name a few. So many food experiences to enjoy and it doesn’t have to be at a restaurant or a café, it could be a picnic at a beach or by the river with freshly bought produce. The options are as varied as your imagination.

Travelling for these food experiences is the essence of culinary tourism; immersing ourselves, sampling the taste of a place, our landscape and culture expressed through food, creating everlasting memories. Worldwide, people want these kinds of food experiences and actively seek them out. Linking food with tourism provides a vibrant platform to promote culture through cuisine.

There is a conundrum, however, as many of our food stories are hidden; people might easily drive straight through Levin and not even know about the asparagus. This leads to lost opportunity and potential disappointment for the culinary tourist whether they be a Kiwi or a traveller from elsewhere. There is a real gap in the information that tells the New Zealand food story.

When I was given the opportunity last year, by the New Zealand School of Tourism, to research this quandary, I spoke to our most-knowledgeable voices across the country asking some thought-provoking questions about the state of things. I interviewed 30 food professionals in a variety of guises: chefs, writers, editors, academics as well as food lovers and destination managers nationally and regionally.

They told me that you don’t see much about our food on billboards or the marketing blurbs about the country. Destination marketers – those people who fill the billboards and write the blurbs – need to acknowledge that food experiences can be exciting, challenging and the stuff that memories are made of. Advocacy about food requires the right people in the right jobs, however. As a Nelson chef and restaurateur insightfully points out, “Development boards need the right people, with the right experience, the right knowledge. It is hard to promote something that you are not at least interested in. The guy who thinks food is fuel is not the person we want heading our development.”

So, our food culture remains a bit of a mystery, not only to visitors but to locals as well. Finding the information is a real challenge and trustworthy information even more so. As Angela Clifford, CEO of Eat NZ, told me, “Visitors want to know where the fish is, they need more explanation about our food story, so they are armed with knowledge about what they are looking for. We have to fold in markets, events, the family that grows the food.”

Kelli Brett, Cuisine Editor, suggests a starting point, “We need an easily accessible, comprehensive, one-stop guide (in digital format) to feed the many different levels of tourism: region by region, including all the stakeholders – restaurants from the high end to the casual dining sector, artisan producers, growers and beverage producers. It has to have something for everyone. Everyone has a story to tell and it needs to be told by a trusted source.”

The irony is that we promote primary produce to the world with gusto but we don’t avidly promote the opportunity to experience it at home. Part of the problem has been our production-driven mentality to food: think milk solids, frozen carcasses and bulk exports. There has been little consideration of food in its own setting.

This lack of focus or even awareness goes beyond international marketing and resonates much closer to home. As Gisela Purcell, Visitor Destination Manager at the Nelson Regional Development Agency pointed out, “Raising awareness amongst locals about how special our food proposition is is really important. When locals really value what we have here, they will talk about it more often and word of mouth will grow.”

My research concluded that it is critical to be able to curate, articulate and disseminate New Zealand’s food stories, to educate and attract both Kiwis and international travellers. We must highlight diverse food experiences to appeal to all markets: high-end, middle- of-the-road and budget. The information should provide the signposts about food experiences and tell the stories of the people and the place that makes those experiences possible.

And then along came COVID-19, hitting the world-tourism industry more severely than a tsunami of any scale. We have gone from a hyper-mobile world with travel being the opium of the people rushing to new experiences, to a world with borders shut and mobility truncated. We have had to reset. Research about disaster shows that post the event, people tend to revert to travel close to home. A high degree of anxiety in the population also leads to a marked decrease in travel. People rethink what is important, reconnecting to roots. There has not been an event since WW2 that has stopped the entire world in its tracks. We don’t know yet the full impact of the disaster or its longevity.

At the time of the level-4 lockdown I was deep in the analysis of the current narratives about food, exploring government policy documents, marketing strategies and media stories. But, there is now a significant shift in that narrative. The New Zealand lockdown experience resulted in a surge of reconnection to our food sources and gardens. Organisations such as Eat NZ began discussing food strategies and our food system. The focus shifted to all the stakeholders (growers, harvesters, processors, retailers, consumers) working together to secure the food future. There are discussions about food sovereignty and food security. Government departments began talking about regional food stories and maps of national food experiences. Advocacy for a Ministry of Food is espoused by writers such as Kelli Brett and Lauraine Jacobs and a Citizenry of Food is called for by Eat NZ.

Tourism is being rethought with sustainability at the forefront and seeking greater benefits to communities. Immersive food-and-beverage experiences connect visitors to places and local people and maybe part of the solution for this reimagined tourism.

Recently I spoke to people around the country to get a snapshot of the changing narratives. Ali Boswijk is the CEO of the Nelson Tasman Chamber of Commerce, so has her finger on the pulse of the business environment. I asked her if the lens is on food right now, how do we ensure that it remains there?

Ali says, “Food and beverage is front and centre right now and there is a real desire to support local suppliers and producers. There is a renewed emotional connection to where people live and to food in its own place.

The opportunity for us right now as a country is to shine a light on food, to elevate its production and provenance so that when our borders open, visitors will have heard the narrative and expect food and beverage to be part of the experience they are looking for. As part of that process we must focus on who comes here, who we want to appeal to. We can’t forget that how we project ourselves impacts on who we attract. The old paradigm must change. We can’t keep on with the adventure-tourism image for the twenty-year-old backpacker. It has to be deeper than that.”

Jody Bloomfield lives in Auckland CBD. She is a food lover and avid traveller who loves soaking up diverse cultural landscapes through food. Before she travels Jody prepares spreadsheets of food experiences – mostly internationally, until now. I asked her, as a passionate consumer, how things have changed for her and partner Peter.

“We are much more focussed on New Zealand; there has been a real shift in our thinking about harvesting and sourcing locally. We recently rented a bach in Mahia and went there solely for the harvest: crayfish, blue cod, kahawai, pipis, mussels. We have also swapped food with other gatherers. Getting as close to the source as possible, we love the Avondale Market for fresh vegetables and a melting pot of people. Taking advantage of the amazing diversity in Auckland has been a focus, asking ourselves what else is out there? Let’s take a tour of our own city through the tiny eateries of different cultures.”

Hamish Saxton, CEO of Hawke’s Bay Tourism, recently advertised for a food-and-wine project manager. The role requires an ‘audit and spatial plan of what is grown and produced, raised and caught, when, by whom, and for which markets; the development of a food-and-wine regional story; an understanding of views from whānau about concepts of food sovereignty, gathering, and tradition; the development of a model that demonstrates the value and investment into the local economy and a map of culinary experiences leading to trail development’.

Hamish says, “Hawke’s Bay is New Zealand’s food-and-wine country and I was intent on that message well before COVID. What changed for Hawke’s Bay with COVID was the funding that became available that enables this role.

To build the food narrative of a place requires that stories be substantiated. Multiple regions are clamouring for their food stories to be told, but can they verify what they claim to be their point of difference?

Hawke’s Bay has an appetite for a food-and-wine strategy that is more than a visitor experience but linked to food and technology, production and innovation.”

So, where to from here? Let’s hope that everyone – from Tourism New Zealand to the regions around the country – rethinks food and beverage. The resurgence in the focus on food in the time of COVID has created a momentum that must be capitalised on. Let’s persuade the ‘food for fuelers’ to see food in a different light. I hope New Zealand’s reimagined tourism – for both local and overseas travellers – places food front and centre.

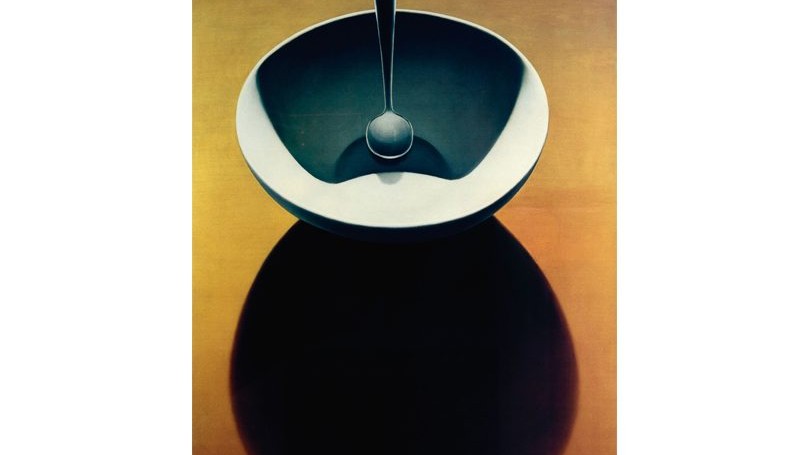

BOWL & SPOON

Michael Smither

Michael Smither was born in 1939 and is renowned as one of the leading painters in New Zealand today.

His paintings are held in public collections throughout New Zealand, including Te Papa Tongarewa – Wellington, Auckland City Art Gallery and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth.

Smither is mainly known for his iconic super-realist paintings and screenprints. He is acknowledged as one of several pivotal painters who emerged in the 1960s, to lead contemporary New Zealand art in new directions.

Also a talented musician and composer, in 1982 Smither developed his own ‘Harmonic Chart’, which he has used as a reference for many of his paintings and sculptures over the past decades. His works can actually be played as a musical score – translating colour into sound.

In 2004, Smither was awarded the CNZM (Companion to the New Zealand Order of Merit) for Services to Art.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Design File / Jessica Crowe / stylist, painter / Whangamatā

Though you may not know Jessica Crowe’s name, if you are a regular…

Traffic July / August 2025

Josh and Helen Emett continue the elegance and success of Gilt, with…