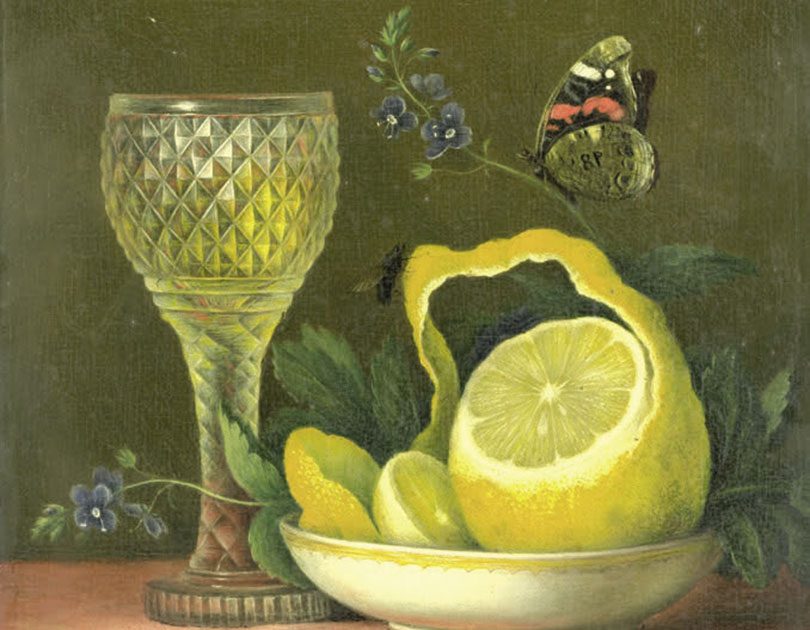

This deceptively straightforward question has fascinated wine writers, philosophers and drinkers through the ages. Does saying a wine is beautiful convey meaning? Is it uselessly vague, or is it attempting to sum up the entirety of one’s experience of a wine? How does it differ from ‘yum’, ‘delicious’ or ‘terrific’? In fact, how precise or exact does wine language need to be?

When asked to define what makes a wine beautiful, we enter shaky ground. Do we describe the wine, or are we being asked to define beauty itself? Does the language we use to describe wine enhance or complicate the aesthetic exercise?

The biggest hurdle for people new to wine is grappling with the specific language used. It covers a vast vocabulary of descriptive, affective, emotive and judgement-laden words alongside chemical, biological and technical terms. To some it’s impenetrable, archaic or even pretentious. The reason we struggle so is because wine is at once sensory, experiential, perishable (once opened) and also highly personal. We experience wine in a very real way but have to translate those sensations and feelings into words.

The chemistry and even sensory aspects of wine are fairly objective. We have even established a sort of collective objectivity when it comes to some of its qualities, though that is increasingly up for debate. Traits such as length, concentration and intensity are generally considered desirable, but more of it is not always better, and concepts like balance are more difficult to agree on. But our individual perceptions diverge and our judgement is almost purely subjective. In reality, we view the taste of wine somewhere between objective and subjective as we process the sensory data using our personal experiences and reasoning.

Do professionals actually describe wines as beautiful? In March 2021, Jancis Robinson MW did an analysis of the 205,000 tasting notes on her database and discovered only 2% of them contained words like beauty or beautiful; which itself is a four-fold increase over the same exercise performed in 2012 on 72,000 tasting notes. And change is a good thing, especially when we stumble across some of the old wine notes with carnal, sexualised, sexist or classist language which would be completely unacceptable today.

Perhaps in response to the unscientific methods of the past, more recent wine education and writing has focussed heavily on measurable characteristics: to establish and reinforce a baseline objectivity for assessment of aroma and flavour (often then backed up with molecular identification of impact compounds), and to measure technical levels of various acids, polyphenols, sugar and alcohols. But we have yet to successfully predict how a wine will taste based on these physical characteristics alone; that requires a judgement from the taster.

But let’s return to the concept of beauty in wine. Is it intrinsic and linked to quality? Is it perceived and therefore subjective? Or, is it the result of an emotional response to the wine’s taste and therefore aesthetic? Much has been written about aesthetics and wine but, as drinkers, we care if a wine is ‘beautiful’ only insofar as it provides us with enjoyment or satisfaction.

In The Magical Science of Taste, season 3/15 of the Wine Blast podcast, Master of Wine Susie Barrie and Peter Richards interview Prof. Charles Spence on the multi-sensory aspects of ‘taste’. He talks about how texture, light, sound and environmental cues can alter judgements of taste, particularly in non-professionals. He references the impact of expectations on the enjoyment of wine and adds another dimension to our understanding of how we aesthetically understand the taste of wine. And that is really key, because it means there is a context involved.

For aesthetic judgements to come into play, we need context and that’s not possible in a purely blind-tasting format which is how wine judging is typically done. So what then is a wine’s context? Is it the people, the stories, the place? Is it the history and therefore does it tie to pedigree? This is one of the aspects of qualitative judgement of wine at a professional level: the ability to sense, measure and then extrapolate a wine’s potential which comes from experience, a sort of admission that there is more than what is discernible in the glass if we know other details about where it comes from or how it usually performs and matures.

But doesn’t this kind of experience exclude the opinions and views of younger wine professionals? Does it not entrench the old and white narrative of the wine world and slow change? Yet we know that even within this environment, change has happened: the composition of wine’s professional bodies has evolved; language has adapted; and the aperture of what ‘great wine’ is has also widened.

This entire confluence of language and aesthetics only makes sense because of why we choose to communicate about wine. I believe it is because we seek to understand, to have a shared experience of life and the things in it which elevate us beyond mere subsistence. So, we are constantly seeking beauty. Perhaps it is because wine calls for sharing that it has played such a strong cultural role. Maybe if we couldn’t share our experience of wine with someone else, there would be no need for it to be beautiful. ■

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Design File / Jessica Crowe / stylist, painter / Whangamatā

Though you may not know Jessica Crowe’s name, if you are a regular…

Traffic July / August 2025

Josh and Helen Emett continue the elegance and success of Gilt, with…