It’s a fish that draws chefs in, that makes diners lean forward. Raw and silky, it’s the pin-up boy of sashimi platters; it’s the luxury line item in every second-rate fusion joint, coarsely chopped and dressed with a citrus, chilli and buttermilk dressing. The fallback for chefs who think raw equals luxury, it arrives as tataki, tartare or poke, or if you’re really lucky, torched. Because nothing says elegance quite like setting fire to your food.

And yet, for all the reverence it commands, most people couldn’t tell you what species they’re eating, where it was caught, or whether they should, in all good conscience, be eating it at all. It’s a fish that demands hard questions about sustainability, seasonality and whether we’re willing to understand the cost of what we’re eating.

In New Zealand, tuna is not one fish but many, each with its own story, each demanding we treat it differently. And so, when I’m asked, ‘Is tuna okay to eat?’, the only honest answer is, ‘It depends’.

Let’s start with albacore which, if you must serve tuna, is the only one you should be using regularly. Caught primarily by surface longline vessels off the West Coast of the South Island, albacore is the most sustainable of the tunas available here. These are smaller fish, ranging between 5-15kg, caught using methods that reduce bycatch and minimise environmental impact. In fact, New Zealand-caught albacore has been recognised by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and is a solid ‘yes’ in terms of sustainability.

It’s also a joy to work with. Handled properly, it’s beautiful. The flesh is pale, lean and delicate, and more subtle than its larger cousins, making it ideal for gentle treatments – thin slices, good olive oil, lemon and a few pink peppercorns or diced into tartare with a dash of soy and citrus, a ponzu, if you will. Or, grilled quickly over charcoal, letting the edges caramelise while the centre stays soft and barely warm. It demands restraint which, if we’re honest, is not a universal trait in commercial kitchens.

Then there’s yellowfin – the tuna of Instagram – all deep-red muscle and #nakedfish energy, the glossy icon of sashimi platters and high-end menus. Caught more widely across the Pacific, yellowfin tuna does show up in New Zealand, though in much smaller volumes. The sustainability picture here is more complex. Some yellowfin populations are under pressure and the environmental impact of large-scale fishing operations can be significant. There are better-managed fisheries, of course, and imported yellowfin that carries MSC certification, but the supply chain matters. Provenance is everything.

If you’re being offered yellowfin, ask where it came from and how it was caught. Line-caught, traceable and a short-chain supply? That’s a yellowfin I can live with. Trawl-caught, questionably sourced, flown in from somewhere vague and far away? Order the chicken.

And now the real heavy: bluefin – majestic, powerful and deeply controversial. Technically legal in New Zealand under quota, Pacific bluefin and Southern bluefin are among the most endangered commercial fish species in the world. Overfished for decades, they’ve become a symbol of everything unsustainable in our appetite for seafood. That said, recent signs suggest the population may be slowly rebuilding.

But bluefin is astonishing to eat. Rich, fatty and marbled like wagyu, it’s unlike any other tuna. It melts. It murmurs. It makes diners weep and chefs preen. This is not something you roll into a spicy mayo and sling across the pass for $14. But it is a fish that comes with baggage. If you’re plating bluefin and calling yourself sustainable in the same breath, well, we need to have a chat. When we talk about sustainability, we too often reduce it to a list: eat this; avoid that. But seafood doesn’t work like that. Not really. Not when you’re standing at the market stall or talking to a fisherman who’s just returned from a week at sea. Sustainability is not a fixed point, it’s a conversation, a series of decisions and a willingness to be informed.

When I serve it (and I do, though rarely), I make sure the story is told: that it came from a quota fishery; that it was handled with the utmost care; that it is precious and should be treated as such. This is not a fish for casual indulgence. It’s a fish for reflection and for reminding ourselves that luxury always has a cost.

Finally, there’s the elephant in the chiller: the word ‘tuna’ itself. It’s used like it means one thing, which it doesn’t. It’s like saying ‘mushrooms’ or ‘cheese’. Tuna is a family of fish, wildly different in flavour, texture, sustainability and status, yet most menus will list it with no context at all. I want to know the species, the method of catch and the story behind it. I want to be able to sleep well after eating it.

For chefs and home cooks alike, the message is this: albacore is your friend. It’s local, refreshingly free of moral dilemma, lean and available fresh during the warmer months. Use it while it’s good and use all of it. Grill the loins, cure the belly, make stock from the bones, and please stop drowning it in wasabi aioli. For yellowfin, be cautious, ask questions. For bluefin, think hard.

Tuna will always occupy a special place in the culinary world. But that place should come with responsibility. Because it’s not enough to serve something that tastes good – not anymore. We need to know why it tastes good, how it came to us and whether it should come again.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Issue 233: Give a man a fish…

Kingfish, whether wild or farmed, spells summer to Martin Bosley.

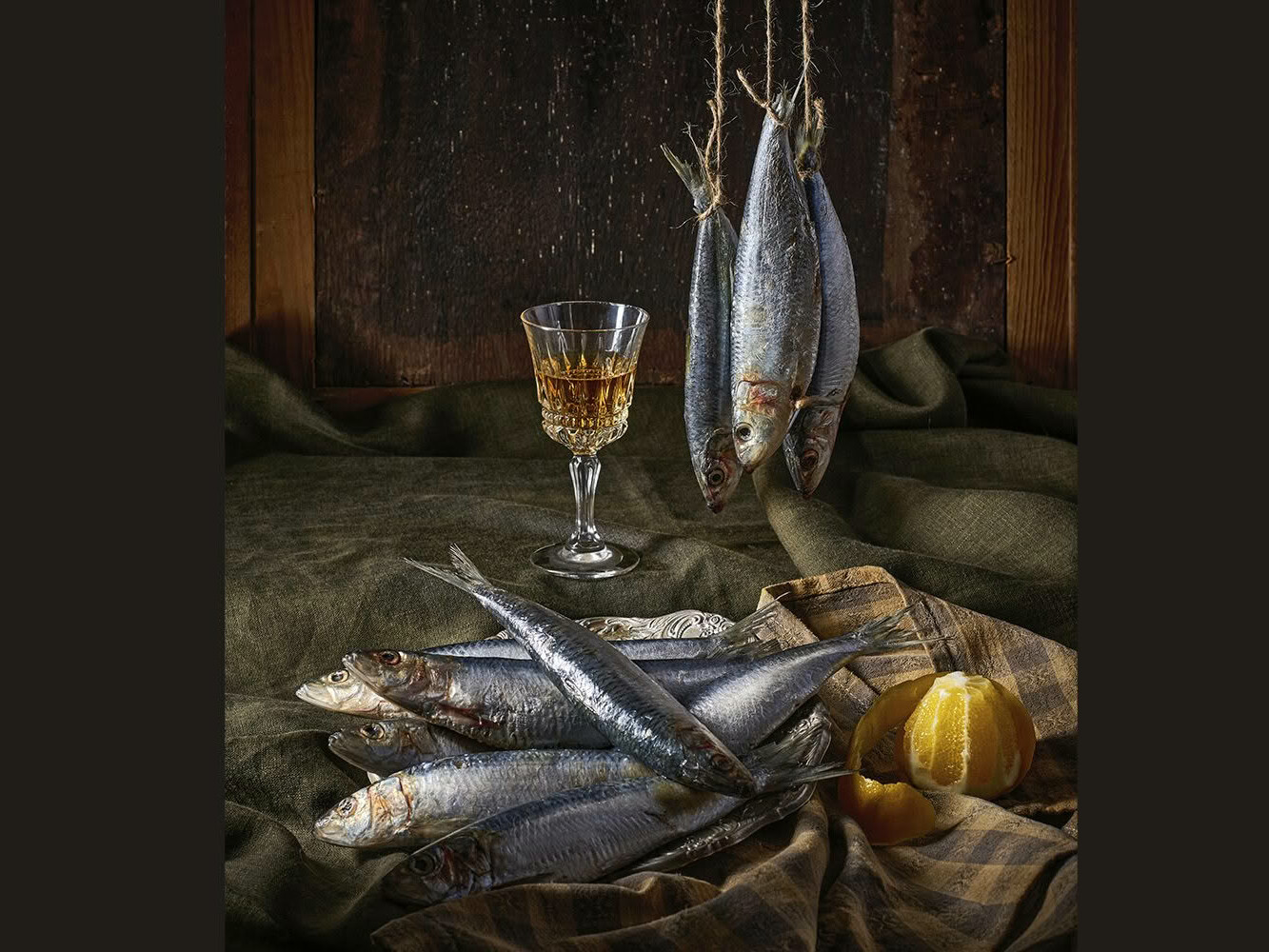

Give a man a fish… Sardines

Sardines: the little fish that could… Martin Bosley urges us to think…

Give a man a fish… Caviar

Caviar: pure luxury or controversial and ethically dubious? Martin…