Martin Bosley takes a close look at the story of our kai moana: its culture, history, issues and sustainability. With the fishing season nearly here, he turns his attention to whitebait.

Come 1 September, from 5am until 8pm, legions of whitebait fishers will be on our rivers in their waders, armed with their nets, fences, guides and optimism, hopeful of catching themselves enough whitebait for a feed of a fritter or two. They will stake their claim on the riverbank, giving nothing away to fellow whitebaiters in terms of catch other than a sidelong glance. The resoluteness of the whitebaiter should not be underestimated; come hell or high water they will be out there. My former mother-in-law, well into her 70s, was fishing after a terrible storm and with the river in full flood the whitebait were running. On one particular large surge of the river she lost her net and she watched in despair as it tumbled end over end, spilling its precious contents back into the river as it was washed out to sea. The only reason she too wasn’t washed away with the net was that she had tied herself to a pine tree on the riverbank.

Whitebait is one of the few freshwater fish we enjoy eating in Aotearoa and anyone can catch it. The set-up is simple, doesn’t cost much and the rewards are worth the effort. It is almost symbolic of a nation steeped in the culture of fishing, from the days of tikanga-based fisheries management through to the quota management system under which we now operate.

Fisheries New Zealand, under the Ministry of Primary Industries, manages the sustainable use of our fisheries through the Quota Management System (QMS) using catch-limits, fishing licences and data collection. Under the QMS, annual reviews are conducted and total allowable catch is set by species and region. The aim of this system is to make sure the fish we purchase at retail and in our restaurants is caught at sustainable levels.

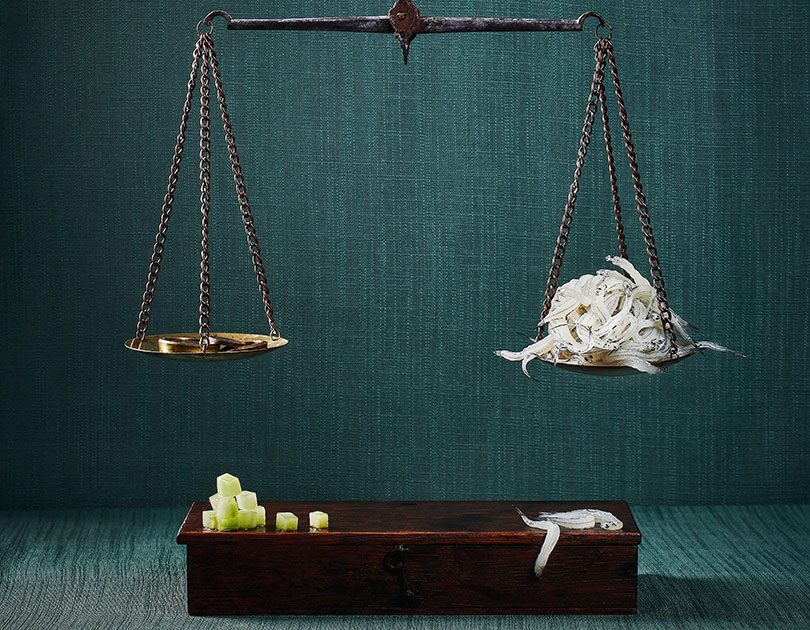

However, management of our native freshwater stocks, such as whitebait, falls to the Department of Conservation (DOC) and some would argue that this management is woefully inadequate. There are no catch limits, no licences and no data collected. When it comes to whitebait, it’s the one fish that restaurants can buy direct from Joe Bloggs, without any purchase records being kept, and at prices of between $70–120 per kg.

The internet will tell you that the five species of migratory galaxiid fish known generically as whitebait are at near- extinction levels, but this isn’t entirely true – we are not down to the very last whitebait just yet. There is no argument that the fishery is under pressure, but just how much pressure no one actually knows. Current understanding is based on ‘snapshots’ of the whitebait life cycle at different places and times and habitat plays an important role.

Steps need to be taken to regulate this fishery and, as at 2022, DOC has reduced the number of fishing days to 60 for the entire country, a reduction from 75 days on the West Coast and 108 days for the rest of Aotearoa (excluding the Chatham Islands). This shorter season is certainly a step in the right direction, but still falls short of what needs to be done; whitebait can still be fished with no catch limit, fishing licence or data collection. Whitebait will only really have a chance when these basic fishery management tools are implemented along with protecting the habitat. In the meantime, recreational fishers (many of whom are catching and selling whitebait at commercial levels) have to be part of the sustainable seafood movement and have just as much responsibility as the commercial fisher, fishmonger or even the chef to think and act with the bigger picture in mind.

Having discussed the ethical issues around the fishery and its cultural impact, it’s time to talk recipes. If I am making a fritter I use one whole egg for approximately 80g of whitebait. First dust the whitebait with the lightest sprinkling of flour so that each fish is individually coated, and then lightly season with salt – do not use any pepper as it is too harsh for the delicate flavour of the fish. Beat the egg in a separate bowl and pour enough onto the floured whitebait to just bind it. Some say that the eggs should be separated, and the whites whipped to stiff peaks before folding them back into the yolks; the choice is yours. Melt a little butter in a frying pan and pour the mix in, cooking each side for about three minutes. Squeeze a little lemon juice over the fritter and serve it preferably between two slices of buttered bread.

In its purest form I prefer my whitebait sautéed. I lightly dust the fish with flour first before putting it into a hot frying pan with clarified butter and a crushed clove of garlic, which results in a pile of deliciously crispy and tender fish. You will need to use a large frying pan because you want plenty of room for the whitebait to become crispy otherwise it can become floury and gluggy. If you don’t have a large pan, cook the fish in two smaller batches, wiping the pan clean between each. A squeeze of lemon juice is all it needs.

While fritters and a sauté are equally delicious, a favourite French classic dish of mine is a paupiette of sole and it takes the whitebait to a new level of class. It’s a quiet, refined dish. The gentle aniseed flavour of dill goes exceptionally well with the delicate, dainty sole. Flounder will also work well here, as would brill and turbot.