CAN YOUR DINNER HELP TO FIX THE FOOD SYSTEM? GEORGIA MERTON SAYS THAT WE ALL HAVE CHOICES

AND THOSE DECISIONS CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.

SUSTAINABILITY – it’s a loaded term that has most of us feeling either smug or vaguely guilty. In the food industry it’s hard to know what it even means, when everybody seems to be flying the green flag. Can a restaurant call itself sustainable only when it grows all its own food? Or uses organic coffee beans? Or can it whack the S word across its menu at liberty, because it makes us feel better?

SUSTAINABILITY – it’s a loaded term that has most of us feeling either smug or vaguely guilty. In the food industry it’s hard to know what it even means, when everybody seems to be flying the green flag. Can a restaurant call itself sustainable only when it grows all its own food? Or uses organic coffee beans? Or can it whack the S word across its menu at liberty, because it makes us feel better?

Asher Boote, owner and chef at Wellington’s Hillside Kitchen, says while sustainability is a hard thing to define, there are plenty of ways to walk the talk. Among its other awards, Hillside has been recognised in Truth, Love and Clean Cutlery, an international guidebook that highlights exemplary organic, sustainable and ethical restaurants.

“Sustainability, to me, means thinking about the ingredients we’re using, where they’re coming from and their long term effect, as well as committing to day-to-day practices like composting all our scraps,” says Boote. The restaurant grows a lot of its own veges, and limits the rest of its ingredients to being sourced within a 250km radius.

To Boote, it’s just as important to be economically sustainable – after all, as he points out, there’s no point doing everything right if you’ll be closed down in six months’ time. Fortunately, many environmentally conscious practices actually make sense financially, too: minimising waste, for example, simply because it is costly to waste food.

It’s an evolving process and Boote says he picks his battles. “We’re not 100% organic, which comes down to access, but we went meat-free last year and we ask all our suppliers not to use plastic packaging.”

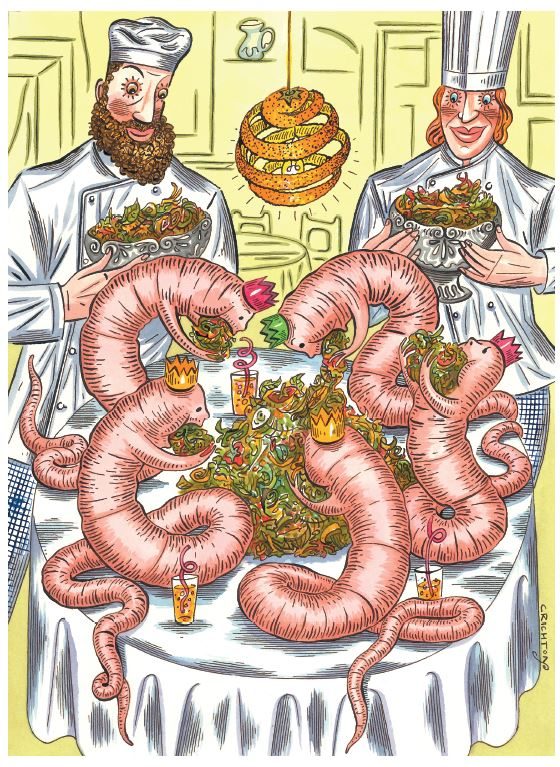

At Gatherings in Christchurch, chef/ owner Alex Davies does everything with the future of the planet in mind. As a chef, Davies sees it as his duty to engage people in conversation around the role of food in reducing carbon emissions. He says we’ve got a broken food system, and uses his approach to show how we can change it.

Also in the Truth, Love and Clean Cutlery directory, Gatherings is plantbased and is filled with recycled timber and artwork. Its produce is sourced locally from organic farmers, and this is more than a marketing line. They have genuine relationships with the people who grow their food, going out to the farm monthly and sending their scraps out to complete the cycle.

Also in the Truth, Love and Clean Cutlery directory, Gatherings is plantbased and is filled with recycled timber and artwork. Its produce is sourced locally from organic farmers, and this is more than a marketing line. They have genuine relationships with the people who grow their food, going out to the farm monthly and sending their scraps out to complete the cycle.

The organic factor, says Davies, is an important one. “I’ve seen firsthand the positive effects that organic farming has on the environment and I know that by putting money into the farmers’ pockets I’m helping it to grow.” When asked about price, Davies says that while increasing demand will see organics get cheaper, we really need to re-look at the way we value food. “After seeing the physical work an organic farmer puts in, versus a tractor spraying everything in sight, I think the way we perceive quality is a bit skewed.”

It’s this connection with food, and the way that it’s grown, that seems to have gone missing. Davies says that when we do reconnect, acting ‘sustainably’ becomes second nature. “I couldn’t imagine throwing something away, when I know it’s taken Gianni and Lorraine [Davies’ suppliers] like nine months to grow that leaf.”

Boote says he thinks it’s our responsibility as consumers to help drive the growth of organic farming. “Look at the recent free-range eggs shortage – the more that people demand these things, the more accessible they’re going to become,” he says. “The thing that’s amazing about organic farmers is the love and care that goes into their food, but there are people who aren’t certified organic who do the same, and they should be celebrated.”

According to both chefs, you can absolutely taste the difference. In fact, this is exactly the way Davies conveys his message, starting by showing people that vegetables can taste really, really good. “They aren’t boring, intimidating, or an ‘alternative’ option. And I try not to be too ‘cheffy’ or overcomplicate things – the hope is that people can take that away and try things at home.”

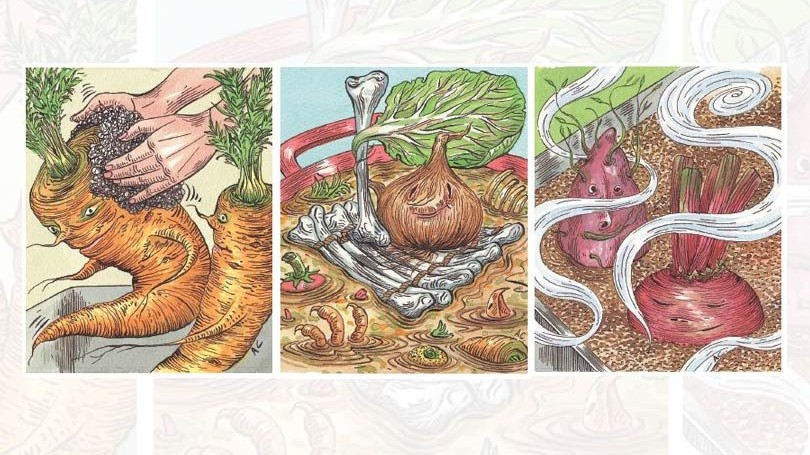

So we arrive at the first way that we, as diners, can play an active role: by following the lead of chefs like these at home. We can start by looking at (and changing) where we get our ingredients from. Are you buying vegetables that are in season? Could you cut down on your meat consumption? Is what you’re buying farmed locally?

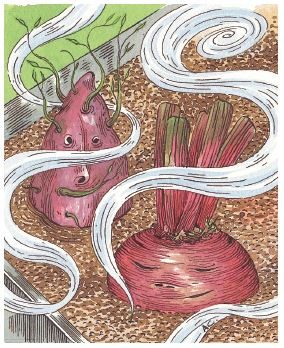

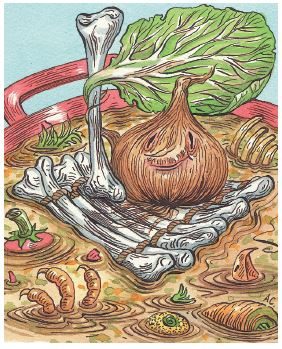

Household food waste is, according to Boote, a much bigger issue than in restaurants: one-third of what we buy goes in the bin. This is an opportunity to get creative and question what we consider as ‘waste’. Vegetable peels? Leave them on or use them in a broth with leftover bones. Coffee grounds? Nestle kūmara in them and bake. Composting what has to be thrown away will create beautiful soil. In other words, we can start walking the talk ourselves.

While this may seem a far cry from the way most people operate across New Zealand, this movement is gaining traction. Everybody Eats is a charitable dining concept that takes surplus food from supermarkets and other organisations, and turns it into restaurant meals. Better yet, they’re using this ‘waste’ to feed Auckland’s most vulnerable people. Customers are allowed to pay whatever they like, even if that means nothing.

Founded by Nick Loosley as a pop-up on K Road almost two years ago, the mainly volunteer team is now also operating three times a week out of its own Avondale restaurant. Loosley is on a mission to roll the concept out, and incidentally, he thinks sustainability is a terrible word. “It’s become overused, which means it loses its meaning and people can start using it when they shouldn’t. It’s so easy to write ‘sustainable’ claims across your menu without following them up,” he says.

Green marketing, as it turns out, is a big issue, and something we need to be wary of. While Davies doesn’t have the answers for how to stop those who simply tick boxes, he says it’s strikingly obvious who’s really living it. “As well as the taste of the food, the staff will be happier – the holistic approach goes into paying your staff well and not taking their social lives away.”

There are, of course, many other ways a restaurant can reduce its impact, from using chemical-free detergent to decreasing portion sizes. And while we may not be able to agree on a definition, we can notice, seek out and champion the work that a growing number of leaders are doing – the Sherwood in Queenstown, for example, which has just been named in Expedia’s list of the world’s 10 most sustainable hotels.

As more people step up to lead the charge on this evolving food movement, we’ve got a chance as diners to get in behind it. We can become more aware of the choices we’re making and start asking questions. As Davies puts it, we need to make as much noise as we can so that people start to imitate this attitude to food. So next time you hear the word ‘sustainable’, let it be fuel to ignite a conversation. Or better yet, let your food do the talking.

One of my favourite uses for spent coffee grounds is to bake root veges buried in them – the moisture steams them and the coffee imparts a wonderful earth, chocolatey flavour (beetroot and kūmara are my favourites).

One of my favourite uses for spent coffee grounds is to bake root veges buried in them – the moisture steams them and the coffee imparts a wonderful earth, chocolatey flavour (beetroot and kūmara are my favourites).- Nukazuke (rice bran pickle) is a great way to use up vege scraps.

- We always peel citrus before juicing to save the zest – either to use fresh or candied for later.

Don’t peel your vegetables, just scrub them and use the whole thing. But if you must, boil them in some water with bay leaves and whatever aromatics you have kicking around and make a good stock.

Don’t peel your vegetables, just scrub them and use the whole thing. But if you must, boil them in some water with bay leaves and whatever aromatics you have kicking around and make a good stock.- Use excess dinner in a toastie or a sandwich the next day.

I’m a big fan of freezing food, if you’re slow cooking, or making sauces or stock, absolutely freeze it.

I’m a big fan of freezing food, if you’re slow cooking, or making sauces or stock, absolutely freeze it.- The other thing is making stock out of bones – you’ve just got to simmer the carcass of a chicken and you’ve got a lovely bone broth which is really healthy and full of umami and beautiful flavour to add to whatever you’re making.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Design File / Jessica Crowe / stylist, painter / Whangamatā

Though you may not know Jessica Crowe’s name, if you are a regular…

Traffic July / August 2025

Josh and Helen Emett continue the elegance and success of Gilt, with…