Kelli Brett receives a plea for urgent change

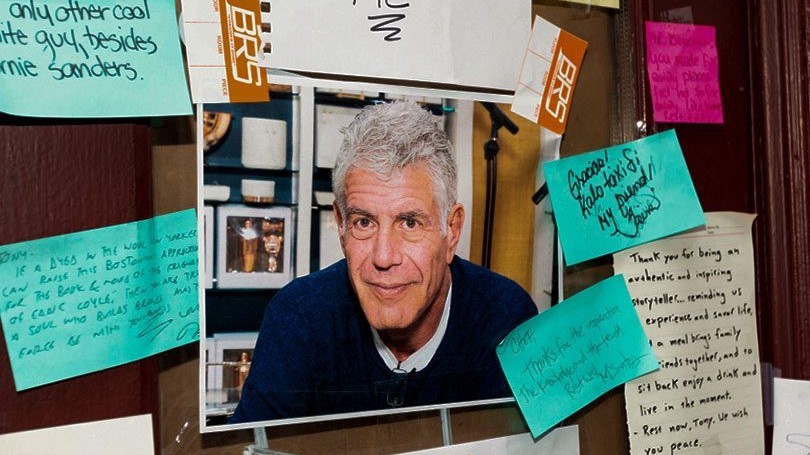

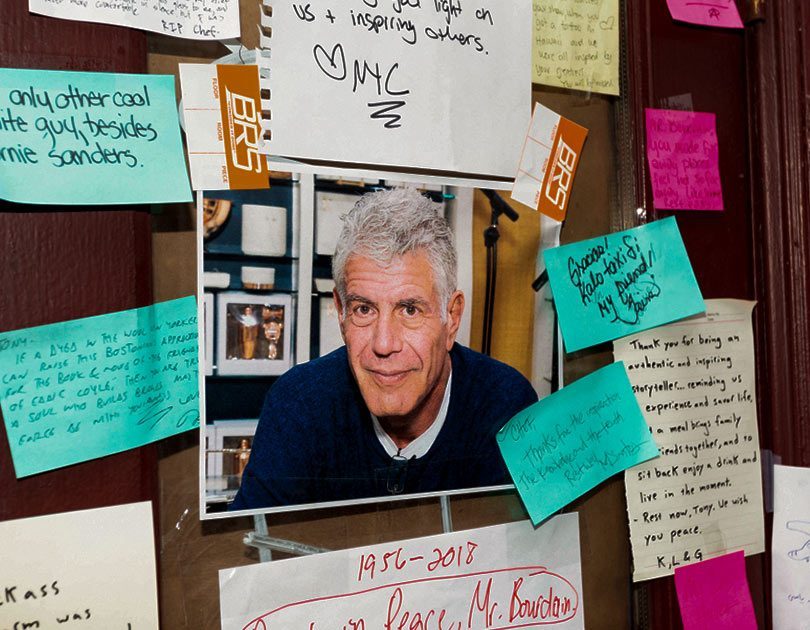

As the incredibly sad news that US celebrity chef and television personality Anthony Bourdain had been found dead of an apparent suicide started to sink in, our social feeds were flooded with reactions from people from all walks of life. The intimate bond that Bourdain had cultivated with millions of readers and viewers was overwhelming. I realised that the hospitality industry would be hit hard: what I hadn’t realised was that my own inbox, direct Instagram, FB messenger and twitter DM would start to fill with messages and tributes from chefs in New Zealand needing to express their shock. Below is an edited excerpt from a piece written by Mitchell Tait, executive chef at three-hat Auckland restaurant, Clooney. Mitchell, I salute you for writing this. Cuisine is working with an action group that was formed earlier this year by the Restaurant Association of New Zealand, to develop a wider conversation about wellness in our hospitality industry. Your words reinforce the importance of creating permanent change.

MITCHELL TAIT WRITES:

Like many aspiring chefs, I read The New York Times’ bestseller Kitchen Confidential when I was young. I gravitated to the world that Anthony Bourdain spoke of and described in such gritty detail; a culture seeping with character and personality.

Ten years on, hearing of Bourdain’s death has shaken me. How could a man with so much wealth, fame and opportunity take his own life? How could the death of a man that I had never met leave me deep in thought for days? The more I thought about it, the more I pondered the current state of mental health in high-end hospitality culture. A restaurant kitchen is a fine line between perfection and chaos. My introduction to this balancing act was as a 16-year-old boy with a cavalier attitude and an arrogant sense of confidence. Many chefs have whimsical stories of cooking with their grandmothers or parents, or growing up harvesting their own food from a family garden. I started cooking simply because I had quit school and needed a job. I was fortunate enough to find work at a good restaurant that took me in like family. I soon fell in love with cooking and the way you could communicate through food – a sentiment often echoed by Bourdain. Working in award-winning kitchens as a teenager didn’t just teach me how to put pretty food on expensive plates. It taught me new levels of discipline, respect, work ethic and focus. It is the basis of who I am as a cook and a person today, so where lies the problem?

Every time the cooking world suffers a loss in the form of a fellow chef’s suicide the same articles are released. The shock-value opening, a small amount of information about that chef and his family, references to other chefs who had previously taken their own lives and hotline numbers at the bottom of articles. The mass media cannot grasp such a complex issue, one so unique and overlooked with bigotry and lack of understanding by the very people who make the industry so rewarding and prosperous. The simple name drops of the late Benoit Violier, Bernard Loiseau or Jeremy Strode: surely these men and all they have done for cooking deserve more respect. Yet when you take a step back it’s easy to blame someone else or focus your energy in the wrong areas. I believe that the focus should be on one’s self to make change and to make small changes in how we approach and treat each other, not wait for someone to hand it to us on a silver platter. These small self-contemplations could be fundamental to fixing a very intricate problem long gone unchecked.

It’s nothing for a cook in a prestigious restaurant to work 12 to 16 hour days; it’s what is expected. The reliance on, or use of, alcohol or recreational drugs is extravagant amongst cooks, wait staff and bartenders alike. There is often a level of pressure filtered down from head chefs or restaurant owners with the constant struggle to stay in the black while maintaining accolades such as Michelin stars, rosettes or chef hats. There is strain on relationships and marriages; the continuous battle to make time for both your career and the people you love; the constant need to be better, not only to satisfy your own hunger and drive but to be better than the chef stood beside you, in order to climb the hierarchy of the kitchen. Make no mistake, kitchens are hot, filled with pressure, and very often verbally – and very sadly – physically violent.

Change in many forms has been seen in recent years: the restructuring of business models to allow a more balanced lifestyle or the rise of the four-days-on-three-days-off working week. Working in collaboration has seen an increase in open information and the sharing of ideas.

I know it seems I have more questions than answers. And that’s because I do. One of the biggest struggles not just in my line of work but with any person suffering from any form of mental illness, or a person feeling lost or defeated, is opening up and talking to someone. I have some very close friends, and the most supportive family one could ask for, yet I still find it difficult to talk to them about how I feel. We need to be doing more. We need to work together to prevent and manage the issues, to open dialogue to normalise mental health and then approach this growing plight on our great industry with vigour, empathy and information.

This was never meant to be a story about the fried-egg-loving, pho-enthusiast chef turned demigod Anthony Bourdain, nor a story about me. In an age where the chef is so often cast as the new rock star, we can easily hide behind our cool tattoos, and mouthwatering Instagram posts. This was something that I was motivated to write as just a chef, in the wake of a tragedy for all cooks everywhere and the overwhelming realisation that positive change is a must.

Chef Mitchell Tait

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Design File / Jessica Crowe / stylist, painter / Whangamatā

Though you may not know Jessica Crowe’s name, if you are a regular…

Traffic July / August 2025

Josh and Helen Emett continue the elegance and success of Gilt, with…