Concerns about sustainability are driving a whole new approach to fishing. David Burton meets the new breed of artisanal fisher and the new heroes of New Zealand aquaculture.

As concerns mount over massive industrial-scale fishing, a growing band of New Zealand seafood innovators are turning to practices such as aquaculture and are looking after local communities better by catching fewer fish using more sustainable methods.

Small-scale fishing is the way forward, says Invercargill fisherman Nate Smith, one of a growing number of seafood reformers who are committed to sustainability by selling smaller amounts of fish directly to local communities and restaurants. But to facilitate this move, says Nate, we need to tweak our Quota Management System (QMS).

He does not question the effectiveness of QMS as a regulator of our fishing industry; indeed, New Zealand and Iceland have actually led the world in this respect by allocating limited catches of fish species based on scientific estimates of their populations, rather than limiting fishing fleets or net sizes as they have tried to do in Europe (without much success). Unfortunately, however, the effect of the QMS has been to concentrate control of New Zealand’s fishing industry to just a few large companies.

“Now, more than ever, we need more artisanal fishers,” said Nate owner-operator of Gravity Fishing, who bases his boat at Bluff and lays his hooks and lines in the waters around Stewart Island, using sophisticated jigging reels that automatically haul in the catch. Yet today, small-scale independents such as Nate have dwindled to no more than a handful.

Celebrated fish-restaurant owner, Fleur Sullivan told Wellington’s Food Hui that when she first moved to Moeraki , there were 18 small fishing-quota holders. “Now there are just four. The heart and soul has been wrenched out of it.”

The reason for this is explained by Troy Bramley of South Wairarapa’s Tora Collective, whose mission is to make high-quality pāua and crayfish available to the nation, rather than send it overseas. The root of the QMS problem, explains Troy, is that fishing-quota holders are permitted to lease out their quota to large seafood distribution companies.

These distribution companies in turn lease this quota out to small-scale fishers, who are obliged to sell their catch to that distribution company. “Why should these middlemen, who don’t even own boats themselves, be able to sub-lease to the small-scale fisher?” he asks.

The leasing of the quota, believes Troy, should be directly from the owner to the fisher, thereby allowing the option of selling to their local community. Nate Smith concedes there is a place for the big deep-sea fishing companies, who often possess quota and operate their own boats, since they are needed for fish exporting. “But we also need to replicate Gravity Fishing all over the country, as a way of giving consumers fresh fish in their own communities.” So Nate has applied to the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) to allow other artisanal fishers to follow his model.

Artisanal fishing

To some extent this is already happening. Along the Kāpiti Coast, two other small-scale fishers, Awatoru and Waikanae Crab, join Gravity in overturning the old mindset of raking over the whole fishery and taking everything. This is replaced with short stints on the boat, catching only a limited weight of fish that has been pre-ordered by restaurants – or in the case of Waikanae Crab, just enough to satisfy the needs of online customers and to fill the display cabinet of their Paraparaumu shop. Owner Matt Whittaker and his partner Narina McBeath only require four or five cases of fish per week to fulfil both these needs.

As their name suggests, Waikanae Crab started out in 1987 by trapping paddle crabs and at one stage had 11 boats around New Zealand fishing into it. However, four years ago, the crabs mysteriously dried up all over New Zealand, forcing owner Matt to diversify into fishing the waters around Kāpiti Island. Five gill nets target specific fish species, but Matt doesn’t set these nets overnight, resulting in virtually no bycatch and fresher fish. No part of the fish is wasted: warehou roe is smoked, the bones are scraped for the fish cakes that Narina makes, while the trimmings from the fillets go into chowder. Fish heads and carcasses provide the stock for the sauce in her old-school fish pies.

High-tech trawling

Gill netting may be one thing, but bottom trawling is quite another. For years, environmentalists have railed against the damage caused by trawling across, or just above, the ocean floor, and the problem of bycatch caught in trawling nets.

Dr Emma Jones, a marine biologist at NIWA, is perfecting a system of underwater filming that would use artificial intelligence to identify species of fish and allow the wrong ones to be drafted out of the net, much like sheep in a stockyard.

Line-catching technology

However, an inherent flaw of trawling is that the fish are often bruised and damaged in the nets. This is why so many artisanal fishers are seeking to achieve quality over quantity by completely abolishing nets in favour of sophisticated line-catching technology.

As Jim Woods of Nelson fishing-equipment importer Beauline International points out, the growth of the hook-and-line fleet is a necessity, being the most sustainable and easiest to manage. It also makes economic sense. “Trawled red cod typically brings only $600 per tonne, whereas line-caught cod fetches $2,500 or more when targeting the right market.”

This is because of its superior quality; line-caught fish is handled far more gently than fish caught in a net and is brought to market much faster and fresher. In some instances such as Lee Fish, a company that fishes the Hauraki Gulf, this also applies to export as the inshore boats are only out for a day or so, while larger deep-sea line-and-trawl vessels can be out for a week to three months, flash-freezing their catch.

Jim is director of development at Beauline, which imports advanced autoline systems, electronic jigging equipment and other gear. The jigging technology, developed in Iceland, allows a line to be set electronically to haul up a predetermined weight of live fish – say 5kg – which means that fish caught are likely to be on the line for no more than a minute.

Such technology should make line fishing (as opposed to netting) more viable for small-scale artisanal fishers, though until now the drawback of this technology has been its expense. While one company currently controls 98 per cent of the market, new competitors are emerging offering more advanced machinery likely to be around 60-70 per cent of the current cost.

Spearfishing

Arguably, commercial spearfishing takes the sustainability of line fishing one step further, in that the spearfisher can pre-select each and every fish that they catch.

The bane of every artisanal fisher is bycatch – accidentally catching fish species for which they have no quota. This means the ‘deemed value’ of every such fish must be paid for, which can prove very costly. Large fish companies may possess quota for such bycatch, which traditionally has provided them with leverage by which they can force small-scale fishers to work for them.

Spearfishing circumvents this problem of bycatch and means that care can be taken not to spear under-sized fish. Moreover, since the hunting is spread over a long stretch of coastline, no single area is over-fished.

Such were the motivations behind the establishment last year of Ocean Speared in Nelson. For more than 18 months, Tim Barnett and a colleague negotiated for the first-ever spearfishing permit issued by the MPI. Over the next three-and-a-half years he can catch butterfish and banded wrasse around the top of the South Island, with every fish measured and the data sent to MPI scientists to assess the impact on various reefs. While banded wrasse is proving a difficult sell to chefs, everybody loves the creaminess of butterfish, which is very similar to blue cod.

Tim works with a deckhand and another free diver. Like many other artisanal fishers, Ocean Speared practises the Japanese technique of ike-jime – using a sharp spike to pierce each fish behind its head immediately after landing it. This causes blood and lactic acid to be drawn out of the flesh and back into the gut cavity, thus avoiding a sour taste in the flesh and slowing rigor mortis so much that another five or six days can be added to its shelf life. The fish are immediately cooled in an ice slurry and later ‘soldier stacked’ in their natural upright swimming position in ice for transportation.

As with Gravity Fishing and Awatoru, all Ocean Speared’s catch is pre-ordered by its client restaurateurs (including the Boat Shed Café in Nelson, Ahi in Auckland and Arbour in Blenheim). By couriering the fish directly to the restaurant, these fishers cut out the middleman and thus obtain a better price, while the chefs receive fresher fish without any handling delays, and in immaculate condition. Well, almost immaculate. Tim Barnett points out that while a shot to the head is preferable, a spear hole through the fillet is all part of the story!

Harvesting clams

Some of the most welcome additions to restaurant menus in recent years have been Cloudy Bay Clams. Using technology developed by company founder Ant Piper, its boats operate just offshore where the surf breaks, using hydraulic winnowing rakes to replicate the action of ocean storms, stirring up the sand to reveal four species of clams that sit in the top of the substrate. The clams are scooped up then moved by water jets to the catch bag at the back of the device.

The catch bag has a certain diameter mesh that sees the clams size-graded on the ocean floor, with only mature clams landed, fit for dispatch to local restaurants and wet markets.

While tuatua were well known to pre-contact Māori, none of the other three species of clam were previously known to exist, meaning names have had to be invented for them (storm clam, moon shell and diamond shell) by Ant Piper. The four species harvested by Cloudy Bay Clams are endemic to New Zealand. Cloudy Bay Clams is proud of the manner in which it harvests, operating sustainably under the quota management system.

The problem with modern fishing technology is that it has become all too efficient and the resultant over-fishing has spawned a global crisis. Consequently, there has been a worldwide move to aquaculture, which now provides more fish for human consumption than fish caught in the wild.

Farming salmon

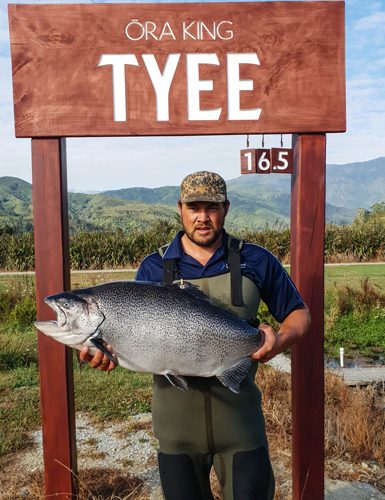

One of the pioneers of fish farming in Aotearoa is New Zealand King Salmon, which has made a virtue of the necessity of having to farm the skittish King or Quinnat salmon (importation of the more docile Atlantic salmon having long been banned). Ever the innovator, the company began selecting superior, well-coloured specimens to form its premium Ōra King brand. Now, however, it has gone a step further and bred the Tyee, a colossal type of King salmon native to Canada, with a more fully developed flavour and more health-giving omega-3 oil, particularly in the belly area favoured by sushi chefs. The fish, which are raised in the Te Waikoropupū Springs in Tākaka, can grow to weigh more than 13kg. The fact that the oil in a King salmon is spread throughout the flesh (rather than being concentrated under the skin as in Atlantic salmon), accounts for its popularity as sashimi.

Farming kingfish

For 17 years, scientists have been experimenting with kingfish farming at NIWA’s Northland Marine Research Centre at Ruakākā, near Whāngārei. Each week about 250kg of kingfish farmed in tanks at the facility has been made available to selected restaurants around the country. Already the feedback from chefs and customers has been overwhelmingly positive. Chefs such as Cameron Knox of Auckland’s Xoong claim the farmed kingfish flesh is firmer in texture and cleaner in flavour, with a rich creaminess that is not found in wild kingfish.

Since September 2020, work has been progressing on constructing a much bigger recirculating aquaculture system that will produce up to 600 tonnes of Ruakākā kingfish per year. If this proves technically and economically feasible, then a full-scale 3,000-tonne operation will follow. A recirculating aquaculture system is effectively a huge aquarium where fresh seawater is circulated through a series of holding tanks, with 95-99 per cent of the water being reused. Compared with the uncertainties of sea-cage farming, this land-based system gives scientists much greater control over the genetics, husbandry and feeding of the fish. The water can be purified and its temperature controlled, meaning disease and parasites can be excluded. By knowing what light patterns and feed type to use, scientists can collect eggs on any day they specify. An egg can be grown to a 3.5kg kingfish in a single year.

Farming toheroa, whitebait & pāua

While mussel and oyster aquaculture is well established in New Zealand, farming our emblematic toheroa, whitebait and pāua has proven far more problematic.

Toheroa – the aristocrat of New Zealand clams whose flavour is influenced by its exclusive diet of plankton – has so far eluded aquaculture, but a team from the University of Waikato is exploring the possibility of growing these giant clams in recycled plastic moulds, which would result in thinner shells and more meat. It aims to establish a pilot toheroa plant at the University’s Coastal Marine Field Station in Tauranga.

Whitebait farming is based on the work of Paul Decker at the Mahurangi Technical Institute in Warkworth, who successfully solved the problem of breeding fish that cross between saltwater and rivers.

Over eight years he, Dr Tagried Kurwie and their team managed to breed all five of the native whitebait species in tanks at the Institute. In 2014, they took the venture to market, launching their first commercial harvest in 2016. Sold under the Manāki brand, this farmed whitebait is available all year round and arguably tastes even better than the wild version, since the tiny fishes’ guts are purged clean prior to harvest.

The story of pāua farming has been rather more troubled, with virtually every past venture having failed to survive the three-and-a-half to four years needed to grow the abalones to marketable size.

At one stage, Paua Fresh near Napier offered small cocktail-sized specimens, which were attractive to chefs both for their elegant proportions and for their exceptionally mild flavour. This resulted from feeding them a plant-based diet, different to the strongly flavoured kelp that is the staple of pāua in the wild. However, there’s apparently no money in baby New Zealand pāua, since tropically grown abalone can reach marketable size in only one year.

Our most enduring pāua farm has been Moana New Zealand’s Blue Abalone operation at Bream Bay, whose pāua is sold to domestic and export customers live and frozen in 1kg bags, and minced in 200g pots.

Down south, meanwhile, a far more ambitious venture is underway. At the heart of the emerging Ocean Beach Aquaculture Park near Bluff is Ocean Beach Paua (Abalone) housed in the former Southern Marine Farms facility. If the new company manages to produce the 20 million mature pāua per annum it promises to deliver by 2024, it will easily become New Zealand’s largest operation.

The wellness market

Since 2002, Auckland’s Pacific Harvest has sold various dried seaweeds (both indigenous and imported) to home cooks, but mainly our abundant kelp has been traditionally processed into soil additives and animal health products, as at AgriSea in Paeroa.

More recently, there’s been a move towards including seaweed in health supplements and beauty products. Christchurch’s New Zealand Southern Pacific Seaweed Company, trading as Oceangreen Organics, markets seaweed health supplements in capsule form and is currently expanding into skincare products and dried seaweed flakes for the table. All the seaweed used is local and fully traceable, with the product’s location coordinates listed on each of their bottles.

At Canterbury’s NZ Kelp, Roger Beattie and his wife Nicki dry large quantities of giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) both as a table condiment, Valére Kelp Pepper, and as an animal feed supplement they call Zelp. It’s a dried kibble that both cattle and sheep lick mainly for its iodine content, but it may also have environmental benefits. Researchers at UC Davis University in California are examining the question of whether feeding cows a little kelp could reduce the amount of methane they burp into the atmosphere.

Christchurch’s long-established Aroma NZ sources and refines green- lipped mussels from its own farms in the Marlborough Sounds, which are sold as a powder to improve joint function. Its mussel oil is said to improve circulation and reduce inflammation, while its abalone powder is claimed to promote a healthy heart and sexual function. Even the lowly sea cucumber is made into a tonic for arthritic pain.

Sanford has also entered into this lucrative wellness market with a mussel preparation, again aimed at providing support for joint health. Its Sea to Me brand uses dried New Zealand green-lipped mussels, which are flash-dried into a powder before being put into capsules in Nelson.

Harvesting seaweed

In the 1980s, Japanese fishing boats accidentally introduced over a dozen different types of wakame seaweed to New Zealand. As the tender, cabbagy varieties are good to eat, it’s not surprising that attempts have been made to harvest these swathes of wakame from around our coastlines. There were early harvests of the wakame that grows as a nuisance on the ropes of the mussel farms in the Marlborough Sounds, but it was found to lack consistency, both in quality and yield. Currently, a feasibility study is underway to see if the quality and quantity of wakame on the mussel farms of the Hauraki Gulf is any better than in Marlborough. This scheme is seeing experimental consignments of wakame exported to Japan, but they face stiff competition from China; in 2019 the export price for its wakame dropped by more than half from the year before.

In view of the current foraging craze, it seems surprising that we have no cottage industry of samphire harvesters to supply our premium seafood restaurants as the wild samphire from East Anglia’s marshes is sent to the posh restaurants of London. Our deliciously crunchy, cucumber-flavoured sea grape (Caulerpa lentillifera) may be too rare to viably harvest from the wild, but some pioneer might decide to cultivate it in ponds, as is done in the Philippines and Japan.

The willingness of New Zealand scientists and entrepreneurs to tackle the farming of even our most obscure forms of marine life shows there is still plenty of room for more innovation. The possibilities, in fact, are endless.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Design File / Jessica Crowe / stylist, painter / Whangamatā

Though you may not know Jessica Crowe’s name, if you are a regular…

Traffic July / August 2025

Josh and Helen Emett continue the elegance and success of Gilt, with…