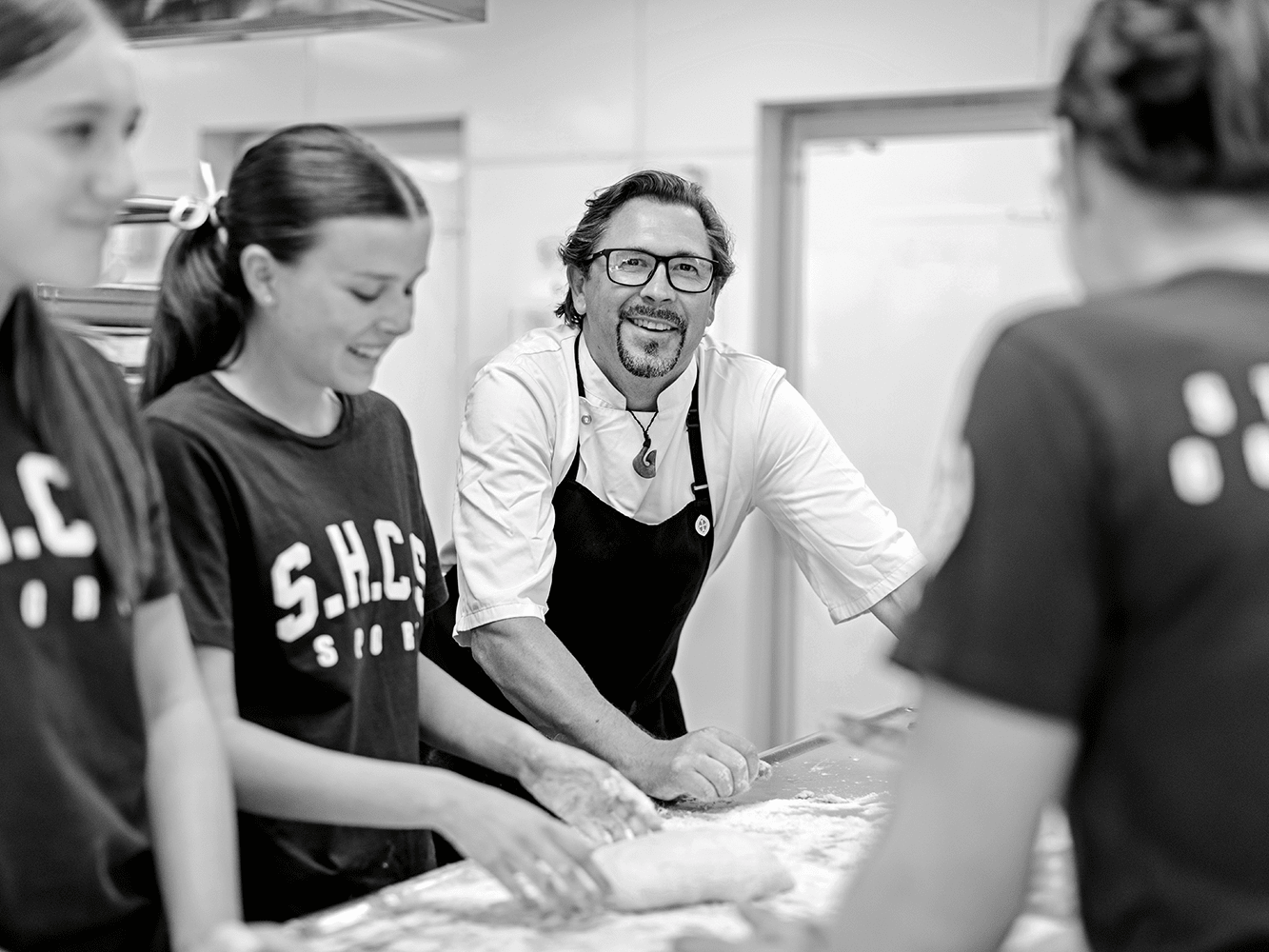

Tracy Whitmey talks to Lucas Parkinson about a new way to run a restaurant and helping our seasonal towns to thrive.

This is a story about economics. But it’s not. It’s about the strength and courage to think ‘what if…?’ It’s a tale of soaring highs when your restaurant wins a coveted Cuisine hat to eviscerating lows when it burns down the next day; of painstaking effort to build up the business again just before the relentless grind of Covid lockdowns; of complete mental and physical exhaustion pushing you to give up all you have worked for; and of having the grit to try a new way of doing things.

“Sometimes when life offers you opportunity you gotta go for it,” says Lucas Parkinson. “The cards fell into place. The powers that be lined this one up. I got that card and I’ve played it.”

Lucas, who readers will remember as the former chef/owner of Ode in Wānaka, is speaking about his new venture Aryeh (pronounced are-ee-ay, ‘lion’ in Aramaic) in Piha, a beach town west of Auckland.

After selling Ode, Lucas didn’t cook for a year. Then some consultancy work in France segued into working with Kiwi chef Nick Honeyman at his restaurant Le Petit Léon. Lucas found himself in Saint-Léon- sur-Vézère, a tiny 11th-century village in the south of France where he was inspired by Europe’s seasonal restaurants: places that thrive during the tourist season then close during the quieter times of year. Tapping into this centuries-old hospitality tradition, Lucas believes, could bring vital energy to New Zealand’s seasonal towns and change the way their hospitality businesses operate.

This is how it works. In the usual business model, restaurants in tourist towns make money during the busy season and lose money in the off season, sometimes struggling to meet their fixed rent payments at times when their turnover is significantly lower. There’s a high churn of hospitality businesses in seasonal towns, thwarting feelings of community and neighbourhood. Lucas learned that in France, rather than paying a fixed monthly rent, it’s common for restaurant owners’ rents to be a percentage of their turnover. It’s a flexible collaboration so if the business does well the landlord does well; if times are tough the restaurant isn’t crippled by high fixed costs.

Back home in Piha the idea settled in. Spotting the vacant premises of the old Piha Café, he pitched the turnover rent idea to the landlord and, somewhat to his surprise, they agreed to his plans: a smart- casual eatery that opens 6 days a week from December to April. Inside will be a 55-seater restaurant for a relaxing three- course lunch or dinner, or a five-course tasting menu. Outside is a casual 35-seater beach bar, walk-ins only, for beers in the sun and something good to eat at a good price. Similar to Ode, Lucas will run a zero-waste kitchen and will work towards becoming fully organic and sustainable. In the months that the Piha restaurant is closed, the space could host pop ups, events or community ventures and Lucas may even have an equal- but-opposite restaurant in a winter town.

“Deliciousness is at the forefront, and making sure everyone is satisfied and leaves with a full belly. I want everyone to feel comfortable – the person that comes in jandals, boardshorts and a singlet will be just as comfortable as the lady in her best dress with her man in a three-piece suit.”

Having experienced brutal working hours and harsh kitchen regimes himself, Lucas is keen to come up with a better way. “We get into hospitality because it’s an interesting and exciting job but there’s a barrage of negativity that comes with the greatness: you lose your passions, you can’t see your friends, your family miss out on events. I wanted to figure out a way to curtail this. We’re a gritty, hardy bunch in hospitality, but I want staff to get a good week’s salary and get to enjoy life as a human outside the workplace.”

So, not content with just disrupting the established costs model, Lucas also plans an innovative approach to staffing. In response to a social media poll earlier this year to hundreds of hospitality workers, 80-90% of respondents told Lucas they would rather work both lunch and dinner shifts for three days (with a couple of hours off in between) then have four days off. So, that’s what he’ll do.

Speaking to Lucas and learning his story, it makes you wonder how he has found the strength to put misfortune behind him and have the enthusiasm for new beginnings. “I’m in a much better place now. I’m damaged from what I’ve been through, and it lays seeds of doubt. It does affect me but I can’t just sit around. I’m overjoyed to be back on my soil. I love these lands. It’s where I feel at ease and at peace, safe in my spirit. I’d rather live a life where I’m trying to highlight the good about things. Now it is time to speak to the positivity.” @aryeh_restaurant

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

We’ve Noticed…. Marcus Verberne

Cooking skills open up a world of different opportunities. From fine…

We’re Watching… Chantelle Nicholson

Tracy Whitmey meets a world-recognised Kiwi chef bringing her…

We’re watching… Angela Allan

Kerry Tyack meets Angela Allan, winner of New Zealand Sommelier of…

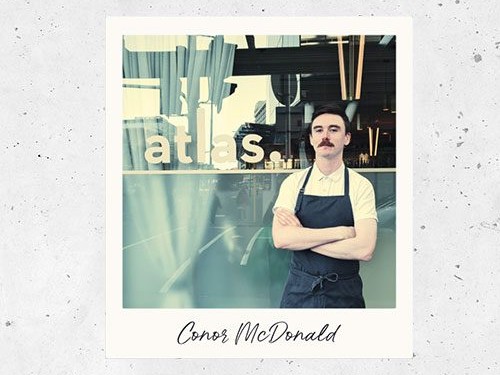

We’re watching… Conor McDonald

Kerry Tyack meets Conor McDonald, an Irish chef who is running hot.